There is something intrinsically enchanting about champagne. Its delicate effervescence, golden hue, and celebratory pop have long made it the drink of choice for life's grandest moments. But beyond the sparkle lies a subtle art to serving champagne that can elevate any gathering from delightful to unforgettable. Whether you're hosting a black-tie soirée or an intimate dinner party, mastering the ritual of champagne service brings an air of sophistication and intention to your celebration.

Select the Right Champagne

Before the cork is ever loosened, elegance begins with selection. True champagne hails exclusively from the Champagne region of France, crafted from a blend of Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Meunier grapes. Each house offers its own expression—from the crisp minerality of a Blanc de Blancs to the richness of a vintage brut.

For celebratory toasts, a brut (dry) champagne is a versatile and widely appreciated choice. For aperitifs, consider a rosé champagne with its delicate fruit notes, while a vintage bottle lends gravitas to a formal dinner.

Remember: while sparkling wines from other regions (like prosecco or cava) can be delightful, the label “champagne” is reserved for the real thing.

Chill to Perfection

Champagne is best enjoyed chilled, ideally between 45°F and 50°F (7°C to 10°C). Too cold, and the nuances of flavor are muted; too warm, and the effervescence may become overpowering.

To chill properly:

- Place the bottle in a bucket filled with equal parts ice and water for 20–30 minutes.

- Alternatively, refrigerate for 3–4 hours. Avoid freezing, as this can dull the flavors and risk an explosive mess when opened.

Choose the Right Glassware

While coupes—the wide, shallow glasses made famous by the roaring twenties—have vintage appeal, flutes or tulip-shaped glasses are preferable for a modern and refined experience.

Flutes preserve the bubbles, allowing them to dance in tight, elegant streams. Tulip glasses, with their slightly wider bowl and tapering rim, strike the perfect balance between preserving effervescence and allowing aromas to gather.

Open with Poise

The opening of a champagne bottle should be a quiet affair, not a loud pop. The goal is a gentle sigh—not a dramatic bang.

Here’s how:

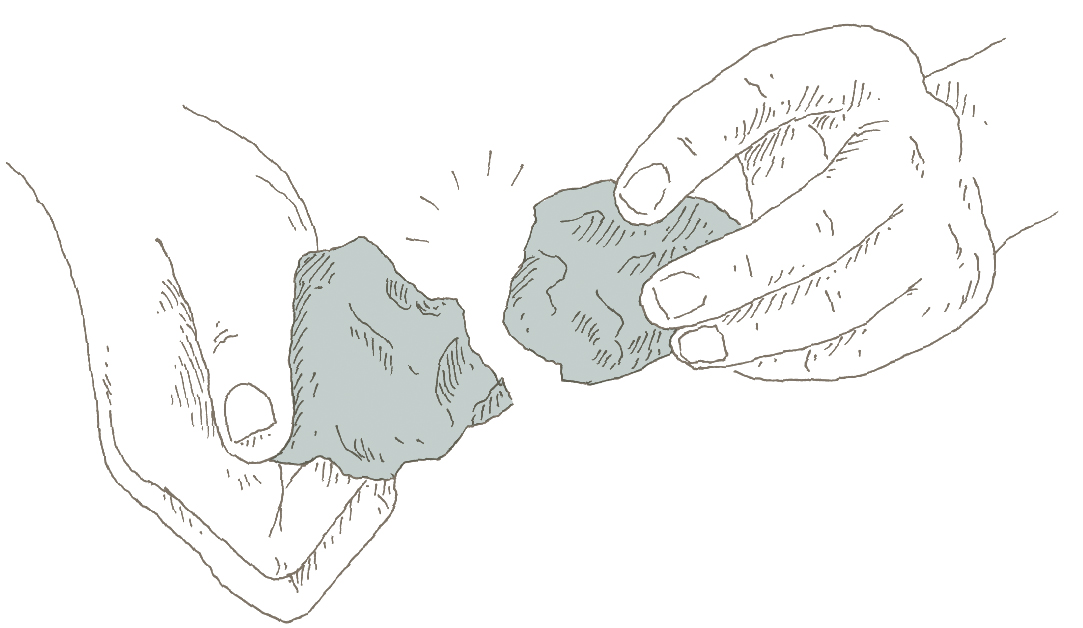

- Remove the foil neatly.

- Keep a thumb on the cork while loosening the wire cage (six half-turns is the standard).

- Tilt the bottle at a 45-degree angle, pointing it away from yourself and others.

- Hold the cork firmly and twist the bottle (not the cork) slowly. Let the gas ease the cork out with a soft sigh.

A discreet opening is a mark of elegance and control. It’s a ritual worth mastering.

Pour with Grace

Hold the bottle at the base or by the punt (the dimple at the bottom). Pour a small amount into each glass first, letting the foam settle, then top up to two-thirds full. This avoids overflow and preserves the bubbles.

If you're serving a large group, pour for guests in a clockwise direction, always starting with the guest of honor.

Serve at the Right Moment

Champagne is both a prelude and a punctuation mark. It can welcome guests, accompany a toast, or elevate a moment at the table. It is not only a drink—it is an experience. Serve it thoughtfully:

- As an aperitif before dinner

- With light courses such as oysters, caviar, or sushi

- With dessert (demi-sec champagnes pair beautifully with fruit-based sweets)

Keep a chilled bottle on standby, and always pour with attentive discretion, topping up glasses gently as needed.

To serve champagne is to offer more than just a beverage—it is to offer a moment. It signals thoughtfulness, joy, and celebration. And when done with care, it adds a whisper of ceremony that guests will remember long after the bubbles have faded.

In the end, elegance is not about extravagance—it’s about attention. To temperature. To timing. To detail. And above all, to the joy of sharing something beautiful.

So the next time the occasion calls for sparkle, serve your champagne not just with confidence, but with grace.